A new economic analysis of the costs of pollution to the United States finds that coal power is harming the economy. In the American Economic Review article “Environmental Accounting for Pollution in the United States Economy,” economists Nicholas Z. Muller, Robert Mendelsohn, and William Nordhaus model the physical and economic consequences of emissions of six major pollutants (sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, ammonia, fine particulate matter, and coarse particulate matter) from the country’s 10,000 pollution sources. They estimate the “gross external damages” (GED) from the sickness and death caused by the pollution, and compare that to the value added to the economy:

Solid waste combustion, sewage treatment, stone quarrying, marinas, and oil and coal-fired power plants have air pollution damages larger than their value added. . .“Five industries stand out as large air polluters,” the authors write, “coal-fired power plants, crop production, truck transportation, livestock production, and highway-street-bridge construction.”

Coal plants are responsible for more than one-fourth of GED [gross external damages] from the entire US economy. The damages attributed to this industry are larger than the combined GED due to the three next most polluting industries: crop production, $15 billion/year, livestock production, $15 billion/year, and construction of roadways and bridges, $13 billion/ year.

When the authors add in highly conservative estimates of the cost of carbon dioxide pollution, they find that “the damages caused by oil- and coal-fired power plants are between 30 and 40 percent higher.” With an estimated social cost of carbon — a damage estimate of global warming pollution — of $65 (far less than other estimates), the GED for coal-fired generators is $0.21/kW.

In other words, instead of being “cheap” and “affordable,” coal is actually the costliest fuel for electricity.

“The findings show that, contrary to current political mythology, coal is underregulated,” Legal Planet’s Dan Farber comments. “On average, the harm produced by burning the coal is over twice as high as the market price of the electricity. In other words, some of the electricity production would flunk a cost-benefit analysis. This means that we’re either not using enough pollution controls or we’re just overusing coal as a fuel.”

Friday, September 30, 2011

Externalities of Coal

Brad Johnson:

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Cost Benefit Analysis of Homeland Security

John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart wrote a book about Terror, Security, and Money: Balancing the Risks, Benefits, and Costs of Homeland Security. Slate Magazine has a series that summarizes their findings. Part 1:

At present rates (and including 9/11 in the count), the likelihood a resident of the United States will perish at the hands of a terrorist is 1 in 3.5 million per year. And the key question, one almost never broached, is this: How much should we be willing to pay to make that likelihood even lower?There have been numerous calls for cost benefit analysis by RAND, the Congressional Research Service, The Government Accountability Office, The National Academy of Science, and many others, but none have been done. For example:

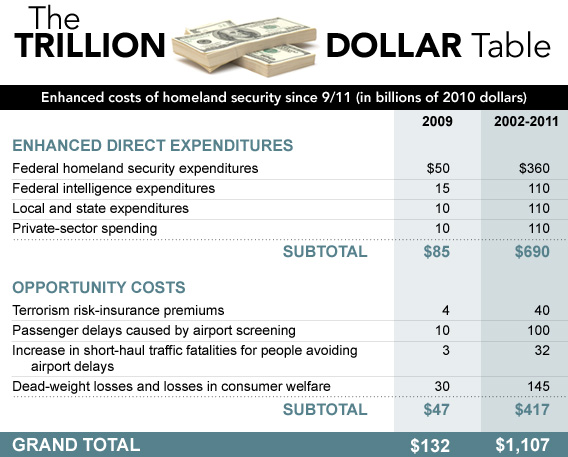

We have, in fact, paid—or been willing to pay—a lot. In the years immediately following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 on Washington and New York, it was understandable that there was a tendency to fashion policy and to expend funds in haste and confusion, and maybe even hysteria, on homeland security. After all, intelligence was estimating at the time that there were as many as 5,000 al‑Qaeda operatives at large in the country, and as New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani reflected later, "Anybody, any one of these security experts, including myself, would have told you on September 11, 2001, we're looking at dozens and dozens and multi-years of attacks like this." ...Tallying all these expenditures and adding in opportunity costs—but leaving out the costs of the terrorism-related (or terrorism-determined) wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and quite a few other items that might be included—the increase in expenditures on domestic homeland security over the decade exceeds $1 trillion. See the following table.

This has not been enough to move the country into bankruptcy, Osama Bin Laden's stated goal after 9/11, but it clearly adds up to real money, even by Washington standards.

In 2010, the department began deploying full-body scanners at airports, a technology that will cost $1.2 billion per year. The Government Accountability Office specifically declared conducting a cost-benefit analysis of this new technology to be "important." As far as we can see, no such study was conducted.Part 2

A recent book by Gregory Treverton, a risk analyst at the RAND Corporation whose work we have found highly valuable, contains a curious reflection:Part 3:

When I spoke about the terrorist threat, especially in the first years after 2001, I was often asked what people could do to protect their family and home. I usually responded by giving the analyst's answer, what I labeled "the RAND answer." Anyone's probability of being killed by a terrorist today was essentially zero and would be tomorrow, barring a major discontinuity. So, they should do nothing. It is not surprising that the answer was hardly satisfying, and I did not regard it as such.From this experience, he concluded, "People want information, but the challenge for government is to warn without terrifying."

It is not clear why anyone should find his observation unsatisfying since it simply puts the terrorist threat in general and in personal context, suggesting that excessive alarm about the issue is scarcely called for. It is, one might suspect, exactly the kind of accurate, reassuring, adult, and nonterrifying information people have been yearning for. And it deals frontally with a key issue in risk assessment: evaluating the likelihood of a terrorist attack.

Treverton's "RAND answer," calmly (and accurately) detailing the likelihood of the terrorist hazard and putting it in reasonable context, has scarcely ever been duplicated by politicians and officials in charge of providing public safety.

...There is also a tendency to inflate the importance of potential terrorist targets. Thus, nearly half of American federal homeland security expenditure is devoted to protecting what the Department of Homeland Security and various presidential and congressional reports and directives rather extravagantly call "critical infrastructure" and "key resources"— assets whose loss would have a "debilitating effect on security, national economic security, public health or safety, or any combination thereof" or are "essential to the minimal operations of the economy or government." It is difficult to imagine what a terrorist group armed with anything less than a massive thermonuclear arsenal could do to hamper such "minimal operations." The terrorist attacks of 9/11 were by far the most damaging in history, yet, even though several major commercial buildings were demolished, both the economy and government continued to function at considerably above the "minimal" level.

...Assessing the threat from homegrown Islamist terrorists, Brian Jenkins stresses that their number is "tiny," representing one out of every 30,000 Muslims in the United States. ...Given this situation, concludes Jenkins, what is to be anticipated is "tiny conspiracies, lone gunmen, one-off attacks rather than sustained terrorist campaigns." In the meantime, note other researchers, Muslim extremists have been responsible for 1/50th of 1 percent of the homicides committed in the United States since 9/11.

...Three publications from think tanks have independently provided lists or tallies of [Muslim extremist] violence committed in the several years after the 9/11 attacks. The lists include not only attacks by al‑Qaeda but also those by its imitators, enthusiasts, look‑alikes, and wannabes, as well as ones by groups with no apparent connection to it whatever.

Although these tallies make for grim reading, the total number of people killed in the years after 9/11 by Muslim extremists outside of war zones comes to some 200 to 300 per year [worldwide]. That, of course, is 200 to 300 too many, but it hardly suggests that the destructive capacities of the terrorists are monumental. For comparison, during the same period more people—320 per year—drowned in bathtubs in the United States alone. Or there is another, rather unpleasant comparison. Increased delays and added costs at U.S. airports due to new security procedures provide incentive for many short‑haul passengers to drive to their destination rather than flying, and, since driving is far riskier than air travel, the extra automobile traffic generated has been estimated in one study to result in 500 or more extra road fatalities per year.

Is it possible to measure the risk of terrorism? Measuring risk can be difficult, but it is done as a matter of course in such highly charged areas as nuclear power plant safety, airplane safety, and environmental protection. There is adequate information about terrorism: There is plenty of data on how much damage terrorists have been able to do over the decades and about how frequently they attack. The insurance industry has a distinct financial imperative to understand terrorism risks to write policies for it. If the private sector can estimate terrorism risks and is willing to risk its own money on the validity of the estimate, why can't the Department of Homeland Security?

A conventional approach to cost-effectiveness compares the costs of security measures with the benefits as tallied in lives saved and damages averted. The benefit of a security measure is a multiplicative composite of three considerations: the probability of a successful attack, the losses sustained in a successful attack, and the reduction in risk furnished by security measures. This product, the benefit, is then compared to the cost of the security measure instituted to attain the benefit. A security measure is cost-effective when the benefit of the measure outweighs the costs of providing the security measures.

The interaction of these variables can perhaps be seen in an example. Suppose there is a dangerous curve on a road that results in an accident from time to time. To evaluate measures designed to deal with this problem, the analyst would need to estimate 1) the probability of an accident each year under present conditions, 2) the costs of the consequences of the accident (death, injury, property damage), and 3) the degree to which a proposed safety measure lowers the probability of an accident (erecting warning signs) and/or the losses sustained in the accident (erecting a crash barrier). If the benefits of the risk-reduction measures—these three items multiplied together—outweigh their costs, the measures would be deemed cost-effective.

These considerations can be usefully wrinkled around a bit in a procedure known as "break-even analysis" to calculate how many attacks would have to take place to justify a security expenditure.

We apply this approach to the overall increase in domestic homeland security spending by the federal government (including for national intelligence) and by state and local governments. ...we find that, in order for the $75 billion in enhanced expenditures on homeland security to be deemed cost-effective under our approach—which substantially biases the consideration toward finding them effective—they would have to deter, prevent, foil, or protect each year against 1,667 otherwise successful attacks of something like the one attempted in Times Square in 2010. In other words, we'd have to foil more than four major attacks every day to justify the spending.

... We have done [estimates] for several specific measures. It appears, for example, that the protection of a standard office-type building would be cost-effective only if the likelihood of a sizable terrorist attack on the building is 1,000 times greater than it is at present. Something similar holds for the protection of bridges. On the other hand, hardening cockpit doors may be cost-effective, though the provision for air marshals on the planes decidedly is not. The cost-effectiveness of full-body scanners is questionable at best. Overall, by far the most cost-effective counterterrorism measure is to refrain from overreacting.

...It is possible, of course, that any relaxation in these measures will increase the terrorism hazard, that the counterterrorism effort is the reason for the low-hazard terrorism currently present. However, in order for the terrorism risk to border on becoming "unacceptable" by established risk conventions, the number of fatalities from all forms of terrorism in the United States would have to increase 35-fold, equivalent to experiencing attacks as devastating as those on 9/11 at least once a year or 18 Oklahoma City bombings every year. Even if all the (mostly embryonic and in many cases moronic) terrorist plots exposed since 9/11 in the United States had been successfully carried out, their likely consequences would have been much lower. Indeed, as noted earlier, the number of people killed by terrorists throughout the world outside (and sometimes within) war zones both before and after 2001 generally registers at far below that number.

...Risk reduction measures that produce little or no net benefit to society or produce it at a very high cost cannot be justified on rational life-safety and economic grounds: They are not only irresponsible, but, essentially, immoral. When we spend resources to save lives at a high cost, we forgo the opportunity to spend those same resources on regulations and processes that can save more lives at the same cost, or even at a lower one. Homeland security expenditure invested in a wide range of more cost-effective risk reduction programs like flood protection, vaccination and screening, vehicle and road safety, health care, nutritional programs, and occupational health and safety would likely result in far more significant benefits to society.

Friday, September 9, 2011

Inflation Indexing, Minimum Wage, Taxes

The Ever-Falling Gas Tax | ThinkProgress:

Federal income tax brackets are “indexed” to inflation in order to prevent “bracket creep” by which real taxes would just rise year after year. But the federal gasoline tax is levied in terms of cents on the gallon and is not indexed, meaning that every year we don’t raise the tax the real value falls every year: Pairing a small nominal cut in the gas tax with a provision indexing it to inflation would provide short-term stimulus while improving policy over the long term.

Cynical Thoughts On The Minimum Wage | ThinkProgress: Arindrajit Dube surveys the post-Card/Krueger minimum wageliterature and concludes that their study basically holds up. My general view, with apologies to empirical econometricians doing policy-relevant work everywhere, is that one can generally Google up a study supporting whichever conclusion one prefers.

Consequently, I’ve always thought the most persuasive evidence on this was simply the big picture:

It’s clearly not the case that the high real minimum wage of the 1960s led to unusually elevated unemployment during that decade. And the fact is even more striking when you consider that the real wages of folks in the top quintile were way lower back then.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)